Pentecost 3 – 9th June 2024 (Christ Church St. Lucia)

Readings: 1 Samuel 8: 4-20; Psalm 138; 2 Corinthians 4:13 – 5:1; Mark 3: 20-35

I want to begin with a brief comment on the first reading and then to spend a bit more time with the Gospel reading which has a couple of difficult passages in it.

Samuel is an old man, and he knows his time is short. He’s been a judge over Israel – divinely appointed. Judges then were more than the judicial appointments we think of now – they functioned as priest, prophet, political leader. He appoints his sons to succeed him, but they are corrupt. It’s been a period of relative stability, and the people turn their eyes elsewhere and see that their neighbours have kings. Working, I think, on the principle that the grass is always greener on the other side, they decide they want a king as well. God says to Samuel, “Don’t take it personally, but tell them what a king will be like.” So, Samuel does just that. He says basically, “You want a king? OK then. This is what a king will do. He’ll conscript your sons. He’ll require your daughters to work in his court. He’ll spend up big on armaments. He’ll levy the best of your land and your produce for his courtiers and flunkeys. In the end, you’ll feel like slaves in your own land.” Well, the people don’t listen. They’re determined to have a king – and they do. And the first king, Saul, is a disaster. Everything Samuel predicts happens. As I read through the reading there are three words that occur like a refrain. You may have picked them up as you listened. They are “He will take.” “He will take.” Our faith calls us to the opposite – to self-giving and service to others. A couple of weeks ago, National Volunteer Week was observed. Across Australia, it is estimated that over 5 million (5.025 million) people volunteered through an organisation or group in 2020. This is almost one quarter (24.8%) of people aged 15 years and over[1]. We can give thanks for millions of Australians who are givers of themselves in all sorts of ways and organisations. We can give thanks for all those who give of themselves to God’s mission expressed through all the pastoral, liturgical and administrative facets of our parish. We can give thanks for leaders who have given of themselves in the service of their peoples – would that there were more.

As I mentioned, the gospel for this morning has a couple of difficult passages, so I thought I might have a go at them. First, to set the gospel reading in some context, it reflects a couple of themes that run through St. Mark’s Gospel. The first is a continuing conflict with the religious authorities which begins very early in Jesus’ ministry and just escalates. Already, in the early part of Chapter 3 read last Sunday, Mark tells us there is a plot hatched between Pharisees and Herodians to destroy Jesus.[2] The second is the whole matter of demons and the demonic. This was very much part of the worldview at the time. Human subjection to the demonic world, led by the prince of demons known as Satan or Beelzebul was all encompassing. Destructive natural events such as storms were attributed to demons. Illness, both physical and mental and moral, was attributed to demons. The Roman occupiers were understood to be instruments manipulated by demons for their own ends.

We have these two themes come together in the passage this morning. Jesus own family think he has lost it, basically. The Greek translated as “gone out of his mind” means literally he is “beside himself.” This of course is an opportunity for the scribes who suddenly appear and accuse him of being demon possessed. He casts out demons by the power of the chief demon, they say. Jesus, of course is more than a match for them and quickly dismisses their argument. How can a divided house stand? He uses a reverse kind of image about someone wanting to plunder a strong man’s house – the strong man must be first bound. And then this difficult statement about those who blaspheme against the Holy Spirit can never be forgiven. What sin can be unforgiveable? Isn’t forgiveness available for all, no strings attached? The Australian commentator Brendan Byrne writes on this passage “the thought of an unforgiveable sin has been a torment for the delicate Christian conscience.”[3] Rather than asking what kind of specific act might lead to such a condemnation, we can look more closely at the passage in context. Since it is by the power of God’s Holy Spirit that Jesus expels demons, to accuse him of doing so through the prince of demons is identifying the Holy Spirit with the unclean spirits of the demonic world. It’s the intentional denial of the holiness of God’s Spirit, confusing good and evil, which Jesus describes as unforgivable.[4] There is an assurance of forgiveness for all when Jesus says, “Truly I tell you people will be forgiven for their sins.” Jesus has come to proclaim the Kingdom of God and to offer the forgiveness linked with the onset of the Kingdom. “The kingdom of God has come near”, he says earlier, “repent and believe the good news.”[5] Only those who identify Jesus’ activity with what is its absolute opposite place themselves out of the reach of God’s saving grace. Who might that be today? Maybe those who misuse scripture to justify acts of violence, particularly domestic violence spring to mind. In my visiting at Greenslopes Hospital for Legacy, a patient recently disclosed to me that an ex-husband had beaten her and quoted the gospel passage about turning the other cheek.[6]

And then Jesus’ natural family appears on the scene – his mother and brothers – and they try to make contact with him. Jesus doesn’t acknowledge them at all but looks at the crowd around him and says that they are his mother and brothers and then goes on to say that whoever does God’s will is his “brother and sister and mother.” The text sets the natural family of Jesus, including his mother on the side of those who misunderstand Jesus and seek to divert him from his mission. We tend to come away from Christmas with glowing, idealized images of the holy family, but Mark paints them in quite a negative light – much more so than Matthew or Luke. It’s not perhaps what we might expect from a Gospel writer. Brendan Byrne notes wryly “If one is looking for a rich theology of family life in the New Testament, Marks gospel is hardly the place to begin.”[7] We like to speak of the “parish family”, but we need to be sensitive as to how we use the term as for some people family is or was hardly a happy place. It’s also clear from today’s Gospel that there were tensions in Jesus own family. What’s going on? It’s possible that Mark wrote his Gospel for a community that was under some threat – the community was probably in Rome – and survival required single minded commitment to the life of the small faith community and sacrifice in many areas of life, so Mark has Jesus highlighting the significance of this for those who would do God’s will.

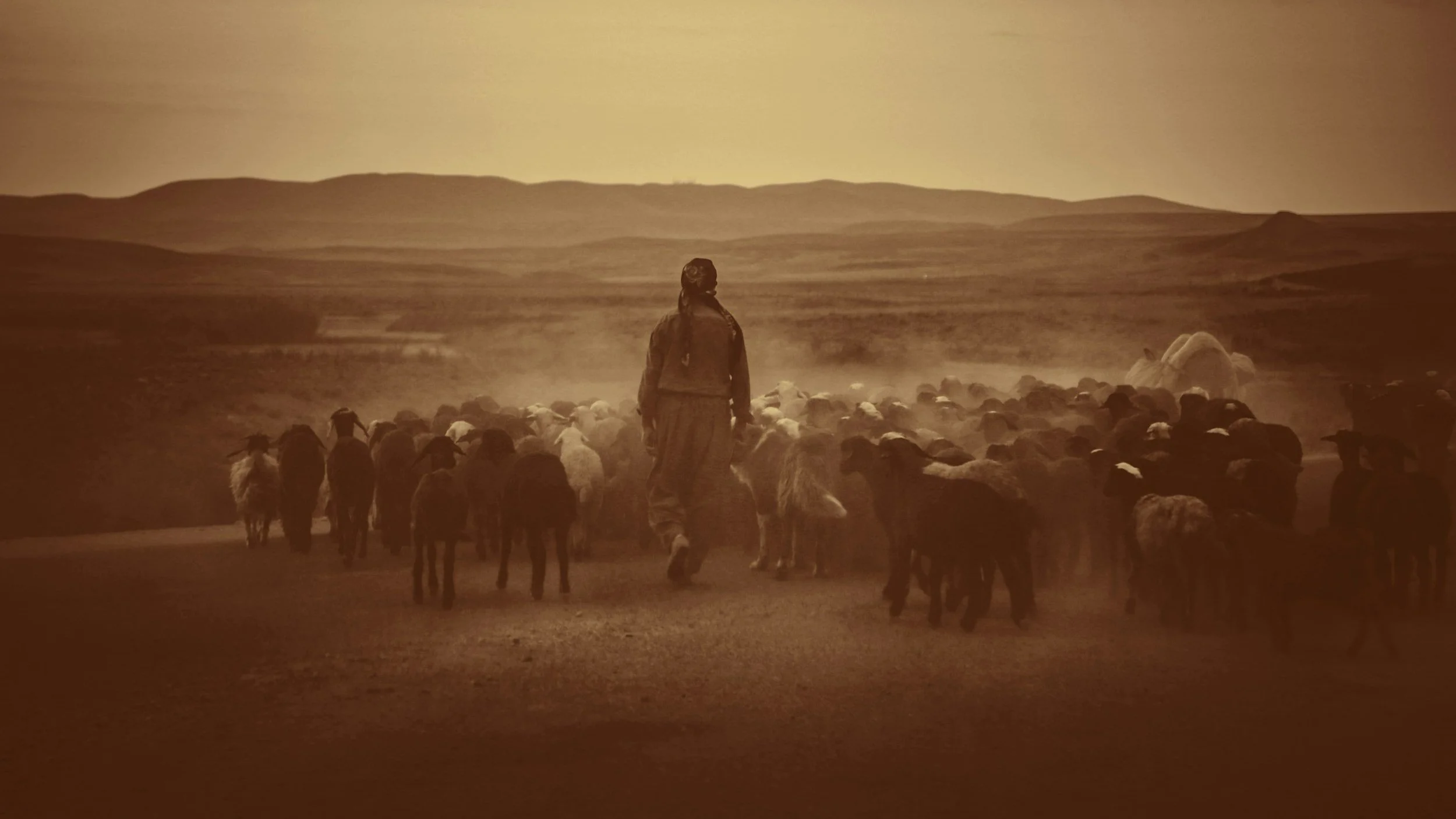

So, it’s all rather a mixed bag this morning. Perhaps one thing that draws the passage from Samuel and the Gospel together is what should characterize this community of the Kingdom, this family of Jesus. And one thing that should characterize us is single minded commitment to service, exemplified for us of course in the life of Jesus, who, ignoring petty argument showed us the way of self-giving, who came not to be served, but to serve. The kind of service encapsulated in the hymn Brother, sister, let me serve you, let me be as Christ to you.[8]

May we serve each other as Christ served us.

©The Rev’d. W.D. Crossman

[1] https://www.volunteeringaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/Volunteering-Australia-Key-Volunteering-Statistics-2024-Update.pdf

[2] Mark 3:6

[3] Brendan Byrne A Costly Freedom – A Theological Reading of Mark’s Gospel St. Paul’s Publications, Strathfield 2008 p74

[4] 3 Rosalind Brown Fresh from the Word – A Preaching Companion for Sundays and Holy Days Canterbury Press Norwich UK 2016 p194

[5] Mark 1:15

[6] Matthew 5:39

[7] Op cit p75

[8] Together in Song No650 – The Servant Song